Running Commentary

On Display

“We reject pedestals, queenhood, and walking ten paces behind. To be recognized as human, levelly human, is enough.”—Combahee River Collective

I was at the coffee shop the other morning, waiting for my drinks, when I felt a presence hovering near me. Though this person clearly had no concept of personal space, I continued browsing my emails, hoping the barista would call my name soon.

Suddenly, the person nudged my arm with theirs, and I looked up to see an older white man with a shaved head grinning at me. He said, “My wife does nails,” gesturing at my feet, “and it’s not often that you see green.” I had gotten a pedicure recently and selected green nail polish.

“Oh,” I replied.

“I love green,” he said, nudging me again. “You’re really pulling it off.” As he looked at me expectantly, I made the judgement call so many of us have to make in situations such as these. “Thank you,” I replied, and laughed.

I went back to looking at my phone, but my quietude had been disturbed. Luckily, the barista called my name. I pocketed my phone and went to the counter to pick up the drinks. As I turned, I avoided eye contact with the man, but then I inadvertently made eye contact with another old white man. I smiled, only because that’s what I usually do when I make eye contact with someone, to acknowledge their presence. As I walked between the men, the second one called out to me, “Wait!” I half-turned to see what he wanted, but he was already going behind me to push open the door for me.

“Oh, thank you,” I said as I walked past. “I appreciate it.”

On Display

The thing is, of course I appreciate when someone is polite or friendly, but so often, the running commentary is not. It’s pretending to be, but it’s not. It’s an assertion of power, a reminder that you are just a little lady and your body is up for discussion no matter where you are or what you’re wearing or who you’re with. Waiting for your coffee? You’re inviting attention with those green-painted nails of yours. Riding shotgun in the truck with your wife? You’re just asking for a car full of young men to yell at you when they catch the sight of two women sitting next to each other on the bench seat of an old Ford pickup.

As James Brown once said, “This is a man’s world.” He went on to say, “But it wouldn’t be nothing without a woman or a girl.” Wow, thanks, sir. The song “It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World” came out in 1966, but you’ll still hear it today. It’s considered a classic, and its attitudes are still prevalent nearly 40 years later.

Cisgender, hetero (and primarily white) men have a sense of ownership over the bodies of others, an assumption that I’m sure dates back to the practice of enslaving other human beings, the “peculiar institution” that has gone unacknowledged and is therefore intrinsically a part of modern misogyny, capitalist patriarchy, and consumerism.

The body is a project, a vessel, to be shaped and punished into the preferences of the Eurocentric perspective. If it does not adhere to these standards, it is exoticized and further objectified, made into a receptacle for all that is wrong with our culture.

Woman as mother. Woman as whore. Woman as Lolita. Woman as bitch. These are the only roles we are allowed to assume.

White feminism objected to the assumption that all women are here to do is have kids and clean the house. The Black feminist tradition objected to the dehumanization of all people.

Black women, who had already been working outside the home, wanted to fight for equality for everyone, including Black men. Our intersectional identities as women who are also Black preclude us from the assertion that all men are powerful and bad, that their maleness protects them from harm. We know this isn’t true.

At the same time, we know that the harm we are subjected to is often at the hands of men, and men who are supposed to love us, protect us. How do we reconcile this? We create our own politics.

The Combahee River Collective (CRC) “develop[ed] a politics that was anti-racist, unlike those of white women, and anti-sexist, unlike those of Black and white men.” They posited that “the personal is political.”

So what does any of this have to do with being catcalled or bothered at a coffee shop? As the CRC said, “sexual politics under patriarchy is as pervasive in Black women’s lives as are the politics of class and race.”

Men bothering me is inextricable from my femaleness, my Blackness. It is in fact because of these identities that I am being bothered, and in the way I am approached. While these men probably thought they were being nice, they were in reality displaying their entitlement: speaking to me, physically touching me, commenting on my body, to even telling me to “Wait.”

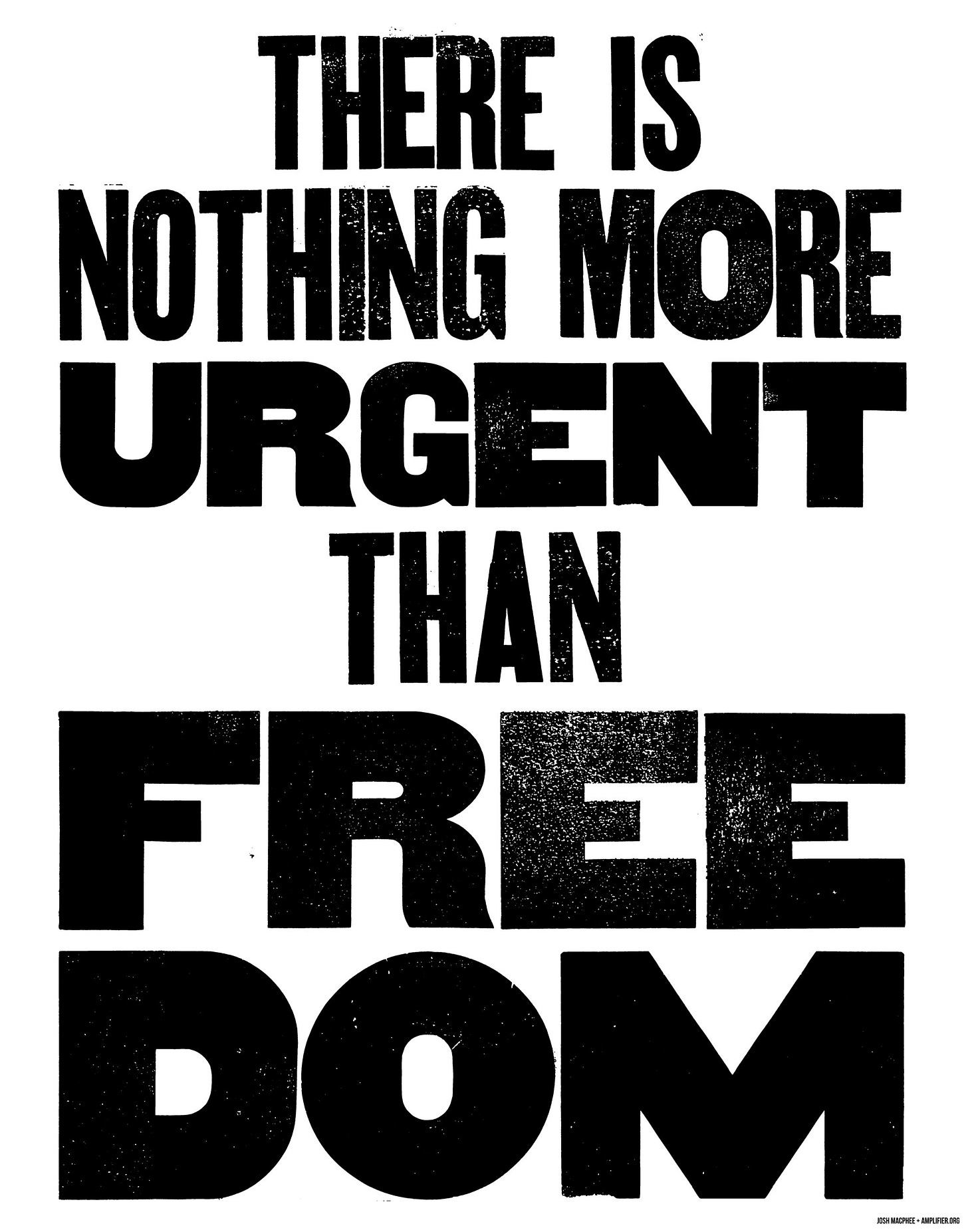

Though I had to make the call in the moment to placate, to pretend, I know that I will not “Wait.”

Whenever I am discouraged by the slow pace of change, by the state of the world, by my brief moments of solace being disturbed, I return to the CBC’s statement and with it, a clear-eyed view of the path to liberation.